Rights on Carpet

Program: Carpet for the event series ‘Everyone a Humanitarian’ at Swissnex San Francisco

Prooject Information:

Client: Swissnex San Francisco

Team: Manuel Herz, Penny Alevizou, Moritz Werner

Jan - May 2017

all photos: © Manuel Herz Architects

Humanitarianism – i.e. activities of support and benevolence amongst individuals – has at its core the belief that mankind is somehow united; that there is something that men and women, independent of gender, religion, race, age or nationality, living across the globe have in common. This commonality is a shared set of values.

Over several centuries, and especially in the last 150 years, a number of declarations, conventions and treaties have been formulated that attempt to articulate what these values are. Amongst the most foundational of these treaties are the Geneva Conventions (1864, 1906, 1929 and 1949), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951).

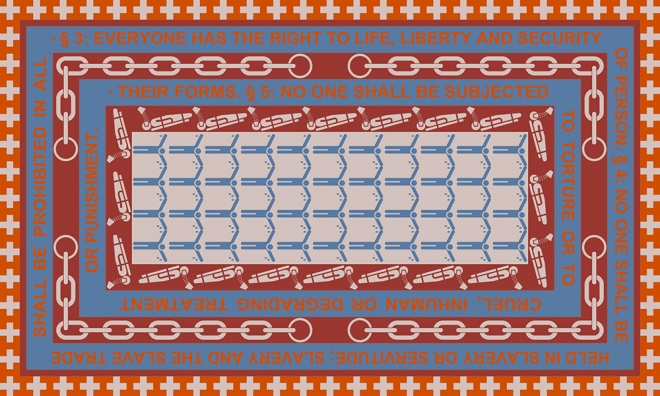

While we might have a certain idea what these rights entail, their exact wording is mostly unknown to us. How is the banning of torture actually formulated? Which words and expressions are used to give us the right to practice our religious beliefs? And moreover, what rights do we actually enjoy?

Especially at a time, when these rights and values have been questioned, and even been grossly undermined, it is crucial for us to recall these treaties, to re-inscribe them into our consciousness, to comprehend their comprehensiveness, and to value the spirit of universality with which they were formulated. The clarity that one reads in the wording for the banning of torture – to name just one example - is striking and puts to shame any attempt to justify ‘extended interrogation’ that we have seen in recent years. The liberties that are afforded to refugees through the Refugee Convention, to name another example, and that has been signed by the majority of the world’s nations, stand at odds with the reality on the ground, and the harassment they can experience, whether it be in Europe or elsewhere in the world.

We are witnessing a moment when rights are more and more considered to be local, particular and the privilege of an elite, when countries are increasingly questioning their international responsibilities, when politicians are openly considering withdrawing from declarations of human rights, and when an appeal to these treaties is by some seen as dated, derided as an expression of political correctness, or even mocked as a symptom of weakness. It is now that we have to bring their source texts back into our general consciousness. We have to remind ourselves how important they are for bringing us together as a shared humanity.

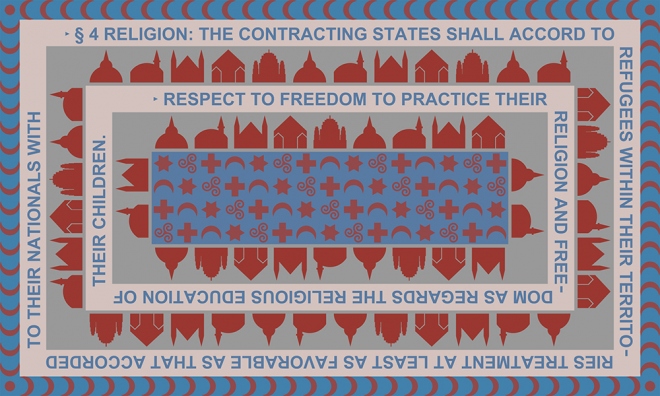

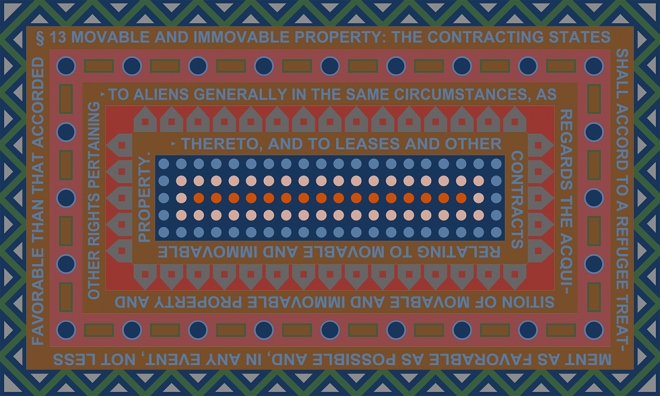

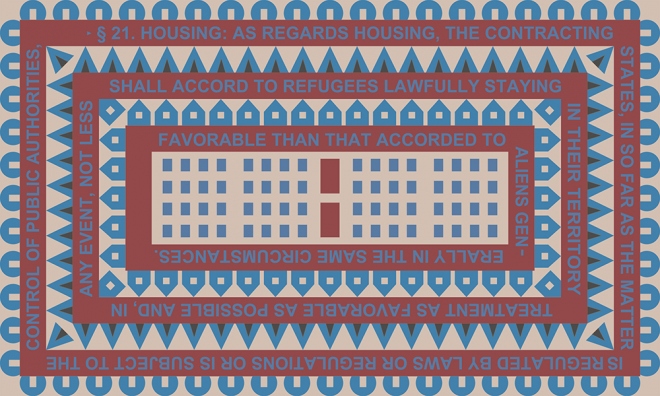

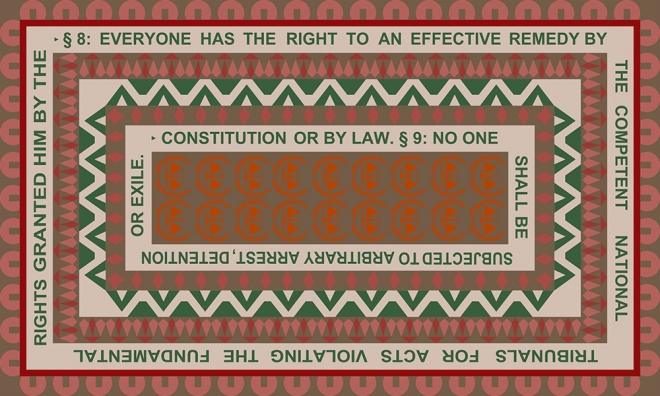

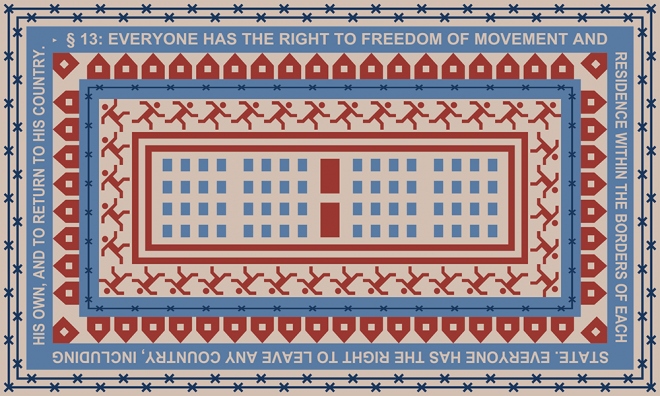

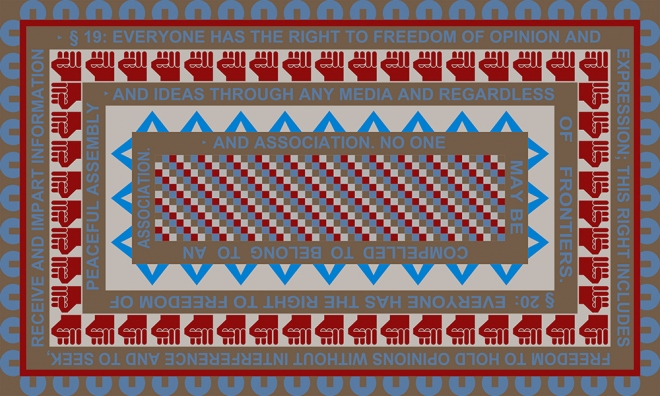

The project ‘Treaties on Carpet’ is a carpet of approximately 150 square meters (1550 sq. feet) that represents four main humanitarian treaties: the Geneva Conventions, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the Convent on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. These texts are written onto the carpet and illustrated through drawings and iconography. While the Geneva Conventions run horizontally across the whole carpet, giving it its main rhythm and substructure, the other three treaties are laid out in three large circles. The circles themselves consist of individual rectangles, each holding the text of one of the treaties’ articles and illustrating it. The rectangles have the dimension that a person occupies when sitting or squatting on the carpet. It’s thematic and geometric arrangement therefore suggests the carpet to be used by informal gatherings or small lectures. The carpet thus starts to trigger and feed discussions and debates around the topic of humanitarianism. It becomes an architectural device for curating the exchange between people.

But there is an additional dimension to the carpet: Everybody using the carpet is obliged to take off his or her shoes. The rectangular areas that the visitors sit in are reminiscent of Islamic praying mats – though in this case not oriented towards Mecca but arranged a circular way. And the activity of sitting in groups and debating and learning about a common topic is exactly what takes place in mosques. Through its design, and the way it is being used, the carpet thus makes every visitor adopt some of the practices of a Muslim. This references the fact that while humanitarian treaties have been denigrated in recent years, at the same time the Western world has also seen the Muslim population becoming the new pariah of our society. Muslims have been portrayed as a threat to Western way of life. Politicians have openly rallied against Muslim population. Muslims are increasingly singled out at security checks, have difficulties obtaining visas, are derided in the streets and public spaces, and are threatened with expulsion, just for the fact of their religion. They have become today’s outcasts. The carpet of human rights thus makes the visitor take on some of the rites of this pariah figure, therefore showing our allegiance to this new group of outcasts. Not only can we all be humanitarians, but we can also all be Muslims.