Published in: Instant Cities, (Ed.: Herbert Wright), black dog publishing, 2008

Somali Refugees in Eastleigh, Nairobi

Refugees often represent one of the weakest and most vulnerable members of a society. They are conceived of as a unanimous mass, warehoused in refugee camps and more often than not can’t decide upon the context and circumstances of their lives. The physical location is a key factor for this powerlessness. Refugee camps are usually located in remote areas. The distance to a social, cultural or economical context limits the possibilities of refugees and creates a dependency on humanitarian aid. Cities and urban regions on the other hand could provide refugees with the potential of exchange on various level and therefore with a certain level of independence. It is exactly because of this reason though – seen as unfair competition by a local population and politicians – that many countries deny refugees their rights to settle in urban regions. A consciously controlled impotence is created, which only strengthens the image of the refugee as a passive recipient of assistance and charity. Urban refugees represent a minority amongst displaced people. Especially in Africa, the continent currently most affected by forced migration, only about 10% of refugees and internally displaced people are settled in an urban context. The few examples of urban refugee communities though paint a different picture to the one of the refugee as parasitical profiteer. Arising from the pressure of self sustainability, their (at times existential) willingness to occupy niches, and the international network that refugees are often embedded in, very complex and lively urban conditions can arise which are of benefit to the local population as well as to the refugees themselves.

Eastleigh

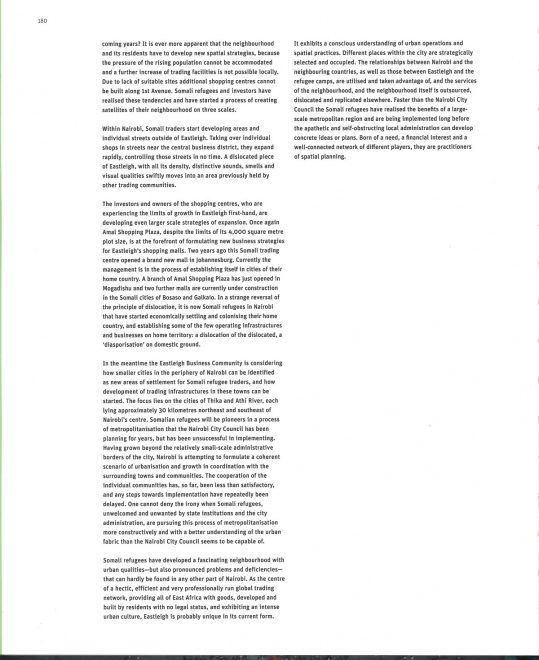

It had been raining throughout the night. The air still wet is saturated with the smell of rotting food and human sweat. Thousands of minibuses and trucks force themselves through narrow streets. Diesel exhaust flows as thick black pulp from the exhaust pipes and fills the air with a nauseating stench. The streets are covered ankle deep in mud. Dense masses of people move and push themselves in a perpetual flow through the narrow gaps left by the cars. Hawkers sell plastic buckets and coat hangers, t-shirts and jeans. Somali street vendors offer household goods or plastic jewelry. The few existing pavements are filled with parking minibuses and pick-up trucks unloading goods or packing them in adventurous constructions on top of the vehicles’ roofs. A continuous strip of shopping plazas flanks both sides of the roads.

‘1st Avenue’ is the main street of Eastleigh, an area of Nairobi located two kilometers east of the city center. Shaped by the dominating presence of Somali refugees, it is one of the most intense and striking places in the Kenyan capital, and at the same time a center of a global trade network. Also coined ‘Small-Mogadishu’ for being a dislocated proxy seat of government of a disintegrated country, Eastleigh with its approximately 100.000 inhabitants represents one of the largest Somali cities, and the second largest contiguous Somali community outside of Somalia itself. Because of the relatively well-established infrastructure in Nairobi, it is assuming administrative functions of the barely operating capital of Mogadishu. A major part of Somali trade is coordinated via Eastleigh, one of the few operating Somali banks has its headquarter in Eastleigh, it is a center of the Somali finance network and location for meetings of Somali ministers and politicians of various fractions to discuss the future of a tragic country. Populated predominantly by non-registered refugees who are not in possession of legal documents, living there informally or illegally, it is a part of Nairobi, located in its very heart, but ignored by the administration of the Kenyan capital, its population “hidden in plain view.”

From an Asian Town to an African City

Nairobi started off as an Asian city. A few years after Nairobi was founded 1896 as a station of the ‘East African Railway’ half way between Mombasa on the Indian Ocean and Kisumu on Lake Victoria, Indian traders started settling in the city. At that time hardly any local Kenyan population was living in Nairobi. Kenyans were only allowed to live within the boundary of the city as bachelors and if they had a formal job employed by one of the white settlers or by one of the companies of the young city. Their families had to reside beyond the city limits in other parts of the country. Indian and Arabic traders who had dominated trade along the east African coast played an essential part in the construction of the train line and were moving with it to Nairobi, especially to Eastleigh. The neighborhoods of the few white settlers in the west of the city, located at a higher altitude, marked by forests, winding roads and an abundance of little streams and rivulets, profit from a good climate and fresh air. Eastleigh, located in the dusty east of the city, was laid out in a chessboard like street pattern, with six avenues in north-south orientation, intersected by 15 streets in east-west orientation. The Indians settling there developed efficient trading structures and quickly dominated most of the trade in the city. A policy change in the 1940s allowed Kenyan families to join their husbands and fathers in Nairobi. This coincided with the growing wealth of the Asian trading community, which was moving to the better neighborhoods of Westlands and Parklands in the west of the city. Eastleigh was thus again to become an “immigrant’s” neighborhood, this time for a population of local Kenyans, all moving into the colonial capital for the first time. With the political independence of Kenya in 1963 segregation of residential spaces along ethnic lines were abolished and the population of Nairobi increases considerably. Along with the Kenyans from villages and rural areas, some Somali traders move to Eastleigh and settle there.

With the toppling of the Somali President Siad Barre in 1991 civil war breaks out in the country at the horn of Africa. Somalia suffers from famine, lack of basic needs, the destruction of its infrastructure, and slides into a condition of anarchy and lawlessness. Within a short period of time hundred thousands of Somalis flee into Kenya. They are placed into refugee camps near the Kenyan city of Dadaab, and eke out a dismal existence in this disconnected part of the country. The Kenyan government, which during the 1980s and 90s had practiced liberal and generous refugee policies and had granted refugees full mobility within the whole country, now opts for much more restricted regulations, when facing the increase of the refugee flow. From now on all refugees have to reside in the camps and are not allowed to take on work. The refugee camps in the east of the country become virtual prisons.

Considerable parts of the people fleeing from Somalia are well-off traders from Mogadishu. They come from an urban background and are not used to the ‘rural’ way of live in the camps. Having sold off their goods and real estate before their escape to Kenya, they arrive with gold and cash. With the lack of trading possibilities in the refugee camps, they start moving to Nairobi. Based on the preexisting contacts with the Somalis that have lived in Kenya’s capital for a longer time, they move into Eastleigh. Thus, for its third time, Eastleigh becomes an immigrant’s quarter, now for Somali refugees who are settling there illegitimately. Initially Somali refugees travel to Nairobi with the aim of settling administrative affairs to quickly move on to London, Dubai or the United States. Guesthouses and other kinds of lodgings are constructed where they pass the time waiting to receive their exit visas. One of these guesthouses is ‘Garissa Lodge’ located on 1st Avenue. The refugees, arriving with considerable amounts of money and often lingering for months before finishing their administrative affairs start spending their time doing business and trading. As they cannot set up their own infrastructure, they just start running business from their hotel rooms. Garissa Lodge slowly transforms from an accommodation space to a trading place. A by now legendary Somali refugee and business woman is the first to recognize this trend, buys Garissa Lodge and completely transforms it into a shopping mall. This nucleus of Somali trading centers in Eastleigh is quickly being multiplied and replicated with many variations constructed along Eastleigh’s central road. Trading acts as an attractor, and the number of Somali refugees in Eastleigh rises quickly, with today an estimated number of 100.000 people living in the streets of “Small-Mogadishu”.

Shopping Malls

The Amal Shopping Plaza currently represents the most developed and sophisticated standard of shopping malls in Eastleigh. Located next to the former Garissa Lodge, recently renamed to ‘Bangkok Shopping Mall’, it is the highlight of retail environments in this urban refugee settlement. Over four floors, products from all over the world are sold for lowest prices. The distribution of merchandise within the building follows a specific curatorial concept. On the ground floor cheap textiles are sold in bulk. The individual shop units, each having a size of approximately 6 sqm, are completely filled from floor to ceiling. Trading takes place in a small niche within the merchandise or in the corridors in front of the store. A functional separation between storage and shopping does not exist. More than 160 stores are offering commodities in this condensed way. Higher quality clothing is sold on the first floor. For 500 to 1.000 Kenyan Shilling (approx. 5 to 10 Euros) one can buy Jeans from China, or T-Shirts for a fraction of the price. On the second floor, two or three single units are joined into larger stores selling shoes, sneakers, dresses or suits. Electronic stores sell TVs, hi-fi systems and mobile phones. The more service-oriented businesses are located on the third floor. Travel agents offer flights to any destination world wide, a Western-Union branch and offices of the global Islamic money banking system – Hawala – can transmit money within minutes to places all over the world and an Afghan fast food restaurant serves excellent lunch next to a local mosque. At the other end of the floor a clinic run by the Aga Khan Trust offers medical services to the local population. The offices of Amal’s general management are located one floor higher, separated from the main shopping center.

The individual levels of the Amal Shopping Plaza are connected by a sequence of intersecting and cascading staircases, ramps, bridges, spiral stairs, elevators, galleries and access corridors. Various internal voids and atriums bring daylight down to the lowest floors creating a complex three-dimensional structure of shopping areas, circulation spaces and communication zones. It is an architecture that simultaneously merges aspects of the informal and vernacular with the highly formalized and conventional. Elements of a standardized repertoire of shopping malls such as galleries and atriums are compressed and densified, and then combined with functions such as mosques, money trading or bulk shopping. Three separate circulation systems exist in parallel and within each other: a complex system of stairways, with cascading flights, intermediate landings and connected bridges that are used as the main circulation system by the majority of visitors; ramps which are used to roll, carry or push the commodities to the individual shops, though also used by the general public; and two elevators installed mostly for representational reasons as they were the first elevators to be built in Eastleigh and symbolize modernity and comfort, though hardly used on an everyday basis. All three systems of circulation are folded into each other, linked and connected, sometimes changing directions, leading upwards and then downwards again. Together with the atriums and galleries they create a complex space of seemingly free movement in any direction and in all three dimensions where shopping, trade, delivery, supply, storage, bargaining, dealing and transactions all take place simultaneously. A shopping center on acid.

The Amal Shopping Plaza was constructed in 2003. Since then a number of additional shopping malls have been built and more are in planning phase or undergoing construction. Shopping malls have identified architecture as a medium of identification and a means to achieve a notion of uniqueness with their customers. They compete with the most expressive facades, shapes of windows, systems of stairs and ramps, as well as with their size, in order to attract more customers.

A Global Trading Network

The civil war that broke out in 1991 and has continued more or less unabatedly has created a Somali Diaspora that extends over the whole world. Somali refugees live all over Africa, on the Arabian Peninsula, in North America, Europe, Australia and East Asia. This Somali Diaspora has, amongst other things, developed a global trading network centered in Eastleigh. Transactions are prepared and conducted via Somali middlemen and contact persons in Dubai, Hong Kong, Minneapolis or London. The merchandise reaches the Somali neighborhood mostly via Dubai and Mombasa, Kenya’s port on the Indian Ocean. Scores of trucks enter Eastleigh daily to supply the individual shops with goods. Neither central distribution points nor storage facilities exist in the neighborhood. As is the case in the shops themselves, there is no separation between retail, wholesale, trade, storage or warehousing. Semi-trailer trucks and 18-wheelers with huge containers squeeze themselves through the narrow streets of Eastleigh, stop in front of a shopping mall, and unload the goods by hand which are then carried through its main entrance and stuffed into the small shop units. Streets are blocked for hours and the traffic repeatedly comes to a complete standstill.

It is not only the merchandise that reaches Eastleigh from all over the world. Because they are able to take advantage of global price differences in their wholesale purchases, due to the low transport costs and the fact that they are often able to evade import taxes, the Somali traders can offer their merchandise at very competitive prices. What started as a local market whose relevance hardly went beyond the extent of the neighborhood itself quickly gained influence over trade of the whole region. By now the group of people who take advantage of the low prices offered by the Somali refugees come from all over Nairobi, and has even grown far beyond. Customers, middlemen and other shop owners come from all of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda into the Somali neighborhood to purchase goods in bulk, which they then resell in their home regions. Eastleigh, this dirty, dense, intense and most striking neighborhood of Somali refugees has become one of the main trading centers of East Africa.

Refugees as Spatial Actors

Somali refugees in Kenya are consciously acting on a spatial level. They have set up a matrix of places, both inside and outside of this host country, and are able to take advantage of the different potentials these locations offer. Structural interrelations exist especially between Eastleigh and the refugee camps near Dadaab, with their 180.000 inhabitants roughly twice the size of the Somali community in Nairobi. Refugee families living in the camps usually send their sons to several places – the town of Garissa located near the camps, to Nairobi, and if possible to Dubai – in order to explore their potentials. Their task is to investigate the financial possibilities, conditions of personal security and general quality of life as well as support the family back in the camps financially. On a monthly basis, sums in the range of 50 to a few hundred dollars – so-called remittances – are transferred from Nairobi back to the families in the refugee camps. Even though their temporary residence might transform into a permanent settlement, for many inhabitants Eastleigh is a place where they can earn money as ‘foreign workers’ to support their families and eventually to return to their home country. As the Somali refugees living in Eastleigh are often registered in one of the refugee camps, they have to return there on a recurrent basis. In regular intervals, UNHCR registers the refugees and performs headcounts in the camps. They are usually announced a few days prior and are of importance to the refugees as entitlements to food rations and other material support is distributed based on this registration. A headcount in Dadaab means big business for the travel and bus companies that are based in Eastleigh offering daily connections to the refugee camps and to many other places all over East Africa. The night before, the streets of Eastleigh are even more congested with people and their luggage, when hundreds, if not thousands of refugees set out to travel through the whole country to be registered by UNHCR in Ifo, Dagahaley and Hagadera, and then drive back again the following day. Even though being one of the most vibrant parts of Nairobi, on a certain level Eastleigh represents a mere outpost of the refugee camps in the east of the country.

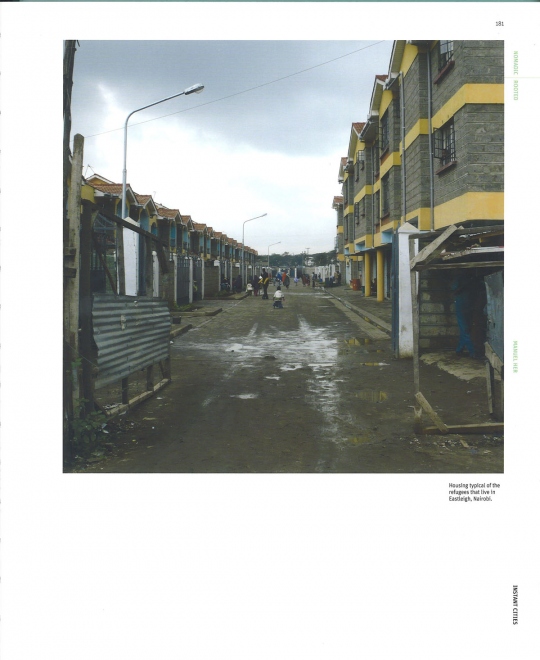

With all the urban qualities, the intensity and the vibrancy that Eastleigh exhibits maybe more than any other area of Nairobi, its quality of life is problematic. The air is heavily polluted by the countless cars, minibuses and trucks. Playing fields for children do not exist, just as there are no parks or recreational areas. Most of the buildings are in bad condition and their sanitary facilities are inadequate. Nevertheless the rent levels have risen sharply in the last few years. Even though occupied almost exclusively by Somalis, many of the residential buildings are not in Somali hands. Today, they acknowledge their mistake of having invested predominantly in trade and not in real estate. Because of the high population density and the fact that living closely together in one neighborhood has a priority for the refugee community, Kenyan landlords can charge almost arbitrary rental fees without relation to the quality of the residential spaces.

As the density is ever increasing, rental fees continue climbing, the quality of life remains unsatisfactory and the lack of expansion area within the neighborhood is becoming more and more obvious, the question arises how Eastleigh will develop in the coming years. It is ever more apparent that the neighborhood and its residents have to develop new spatial strategies, because the pressure of the rising population cannot be accommodated and a further increase of trading facilities is locally not possible. Due to lack of suitable sites additional shopping centers cannot be built along 1st Avenue. Somali refugees and investors have realized these tendencies and have started a process of creating satellites of their neighborhood on three scales.

Within Nairobi, Somali traders start developing areas and individual streets outside of Eastleigh. Taking over individual shops in streets near the central business district, they expand rapidly, controlling those streets in no time. A dislocated piece of Eastleigh, with all its density, distinctive sounds, smells and visual qualities swiftly moves into an area previously held by other trading communities.

The investors and owners of the shopping centers, who are experiencing the limits of growth in Eastleigh first-hand are developing larger scale strategies of expansion. Again it is Amal Shopping Plaza that, being limited to a 4.000 sqm plot size, is at the forefront of formulating new business strategies for Eastleigh’s shopping malls. Two years ago this Somali trading center opened a brand new mall in Johannesburg. Currently the management is in the process of establishing itself in cities of their home country. A branch of Amal Shopping Plaza has just opened in Mogadishu and two further malls are currently under construction in the Somali cities of Bosaso and Galkaio. In a strange reversal of the principle of dislocation, it is now Somali refugees in Nairobi that have started economically settling and colonizing their home country, and establishing some of the few operating infrastructures and businesses on home territory: A dislocation of the dislocated, a ‘diasporization’ on domestic ground.

In the meantime the Eastleigh Business Community is considering how smaller cities in the periphery of Nairobi can be identified as new areas of settlement for Somali refugee traders, and how development of trading infrastructures in these towns can be started. The focus lies on the cities of Thika and Athi River, each lying approximately 30km northeast and southeast of Nairobi’s center. Somalian refugees will be pioneers in a process of metropolitanization that the Nairobi City Council has been planning for years, but has been unsuccessful in implementing. Having grown beyond the relatively small-scale administrative borders of the city, Nairobi is attempting to formulate a coherent scenario of urbanization and growth in coordination with the surrounding towns and communities. The cooperation of the individual communities has so far been less than satisfactory, and any steps towards implementation have repeatedly been delayed. One cannot deny the irony when Somali refugees, unwelcomed and unwanted by state institutions and the city administration, are pursuing this process of metropolitanization more constructively and with a better understanding of the urban fabric than the Nairobi City Council seems to be capable of.

Somali refugees have developed a fascinating neighborhood with urban qualities – but also pronounced problems and deficiencies – that can hardly found in any other part of Nairobi. As a center of a hectic, efficient and very professionally run global trading network, providing all of East Africa with goods of daily needs, developed and built by residents with no legal status, and exhibiting an intense urban culture, Eastleigh is probably unique in its current form. It exhibits a conscious understanding of urban operations and spatial practices. Different places within the city are strategically selected and occupied, the relationships between Nairobi and the neighboring countries as well as between Eastleigh and the refugee camps are utilized and taken advantage of, and the services of the neighborhood, or even the neighborhood itself is outsourced, dislocated and replicated elsewhere. Faster than the Nairobi City Council the Somali refugees have realized the benefits of a large-scale metropolitan region and are implementing it long before the apathetic and self-obstructing local administration can develop concrete ideas or plans. Born of a need, a financial interest and a well-connected network of different players, they are practitioners of spatial planning par excellence.